*

Hamlet, Laurence Olivier once fliply said, was the tragedy of a man who couldn't make up his mind. Same thing with Joe Bonaparte, the Golden Boy bowing Dec. 6 at the Belasco where he initially debuted 75 years ago. Joe's dilemma, which goes the full three-act distance: he can't decide if he's lord of the rings or lord of the strings.

Speeches do not roll trippingly off the tongue here, as Olivier had implored, but come in rude, blunt blats and splats like a tommy-gun out of the '20s and '30s. This is Clifford Odets shooting from the lip, talking tough, cracking wise, hammering out some pretty hard-bitten characters for the legendary Group Theatre to put across.

A gang working out of Lincoln Center Theater, under the exacting hand of director Bartlett Sher, does an affectionate facsimile of that hard-line style of acting, and you might well find yourself transported back three-quarters of a century to that bygone day when Odets' motley Depression-ridden crew first materialized on this very spot.

Sher spilled his secret, such as it was, at the after-party held a few doors west on 44th Street at the Millennium Broadway Hotel. Essentially, it comes down to the same technique that he employed on Lincoln Center's 2006 Tony-winning revival of Awake and Sing! (also cozily ensconced in the rococo splendors of the Belasco). "I think the 'style of acting' is go for the truth and stick with it, and you're fine," he advanced simply. "The language comes after. You have to keep going into the details and into the truth, and you have to be very attuned to rhythm. You can't pick up speed until you're ready. I don't know if I could turn it into a named style of acting — except the same one the Group Theatre had, which started with Stanislavski: how to play actions, how to keep yourself moving ahead, all the normal things.

"If you're around the way I work, I start the conversation and make everybody have the same conversation I'm having, so they find their way under the page with me. I'm very honest. I don't have all the answers, but I guide the conversation, so we're all having the same conversation. We're asking the questions together, so they 're feeling the building of the logic of the piece with me, and it grows from there."

The gritty realism from all hands helps camouflage a conflict that never really materializes on the printed page — the improbable, if not downright impossible, struggle of a violinist who would be a boxer. How many of those do you know?

When first we meet Bonaparte, the sensitive musician in him has retreated from sight. He's a young brute who just decked a boxing contender in a sparring match and brazenly applies for the job from the fighter's manager, Tom Moody. Not only does he get the spot, he gets Moody's quasi-fiancee, Lorna Moon, as well. It all makes you wonder how far Eve Harrington would have gone with a few boxing lessons.

The only semblance of his musical past occurs when his father waves a violin under his nose, prompting him to go offstage and play a heart-stopping concerto, before returning to planet earth and the nasty nitty-gritty of the fight game. Nine years later, Odets made amends for the missed violin sessions here by adapting Fannie Hurst's "Humoresque" into a spectacular Joan Crawford sudser in which John Garfield (who played brother-in-law to Luther Adler's Golden Boy in the original production and the title role in the 1952 revival) was an ambitious career violinist.

Buy this Limited Collector's Edition |

Casting the play properly took six months, according to Sher. "Casting is a mixture of good luck and time," he said. "You have to be willing to take the time to find people."

Since Odets is the personal favorite playwright of Andre Bishop, who co-produced the play with Bernard Gersten for Lincoln Center Theater, time was allowed, and Bishop is pleased with the rough-hewn world that emerged. "These actors have been directed to be real and to reach deep into themselves," he said. "It sounds like what everyone says, but it's not what everyone does. A lot of the cast are New York born and bred — in Queens, Brooklyn, The Bronx — so they know how to do it."

They were music to the ears of Yvonne Strahovski, who managed the tart-talking Lorna Moon with the greatest of ease and assurance, despite the slight handicap of hailing from Australia. "That's a credit to Deb [Deborah Hecht], our dialogue coach," the actress happily acknowledged. "She really helped us along the way. Also, we all watched a lot of old movies. And then also being around each other — hearing all the authentic New Yorkers in the cast, it was a big help to be around them."

| |

|

|

| Yvonne Strahovski and Danny Mastrogiorgio | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

The hard-driving pace of the play is established immediately with an intimate argument between her character and Moody, played by Danny Mastrogiorgio. They come out of the chute, shooting sparklers, slinging attitude all over the stage.

"Odets' dialogue is what does it," Mastrogiorgio contended, "and Bart was very conscious of the pace and the fact that the dialogue works in a particular way.

"The thing I like about Moody is that he doesn't stop fighting. He doesn't stop trying. Things may be bad. They may have been better before. He might have fallen on to hard times, but that does not stop him from trying. I think he is extremely capable of love. His love for Lorna is very true. He doesn't necessarily always do the right thing, but I think he has a lot of heart and comes from the right place, and he never quits."

| |

|

|

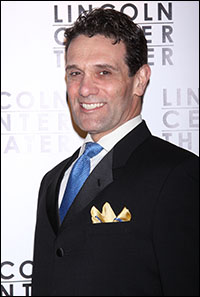

| Anthony Crivello | ||

| photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

"So was Lorna. I went to L.A. and saw everybody I could. Yvonne, initially, was quite a risk because she had training from Western Sydney in Australia, but she had a beautiful warmth and honesty about her — and verbal skills. Also, she can do that weird mixture of tough and vulnerable, and not everyone can do that. She hadn't been on stage in a long time. The first Broadway show she's ever seen or been anywhere near is Golden Boy. This one. She has never even seen a Broadway show."

Crivello soft-peddles the gayness of his characters, painting him in a light lavender pastel. "It's a fine line to walk. He's such a difficult, complex character. The thing is, just from doing research, there was a case in 1935 where two mobsters were killed by the mob in a Milwaukee nightclub called The Gay Spot — the exact same time period of this. [My] character is so audacious and so powerful — he wears it, but he wears it subtly. There is, at times, a flippancy that will come out of him. He's obviously funny. He wants to command the room, but he's also ferocious. It's delicious material to play. It's such a classic piece of American theatre. It's so important that Odets and this particular play be part of a rediscovery of this play on Broadway. I can't convey how humbling it is.

"I had a tremendous time doing this," he continued. "It has been nothing but wonderful being back in New York and back on Broadway. Repeatedly, people are saying to me, 'Anthony, welcome home.' And that's exactly how I feel. And to be in this company with this caliber of talent, to me, is absolutely mind-blowing."

| |

|

|

| Michael Aronov and Tony Shalhoub | ||

| Photo by Joseph Marzullo/WENN |

Like most of the cast, he was delighted to be in that number. "It is an extraordinary cast — a very cohesive group, led by a visionary director. We all just love and trust this material so deeply that it has been a joy to come in every day."

Shalhoub is coming in for some kudos by himself on Dec. 9 in a gala benefit at the Plaza Hotel. "New York Stage and Film is honoring me — I'm not sure what for — I guess for just surviving the business for 30 years. Friends of mine that I went to graduate school with now head New York Stage and Film asked me if I would be the honoree, and I said yes. A lot of other people must have turned it down this year."

Ned Eisenberg and Jonathan Hadary, who previously inhabited Odets' Awake and Sing! on Broadway, color up some subsidiary characters and get laughs doing it.

"He's a beautiful character," Hadary said of the Schopenhauer-quoting neighbor of the Bonapartes. "We were in rehearsal, and I said, 'Wait a minute, I really only know his name from lyrics. He's in Lorenz Hart's 'Zip.' He's in Ira Gershwin lyrics. It's an easy rhyme. He had become by then passé, but he enjoyed a resurgence of popularity between the wars." Ordinarily a musical-theatre reliable, Danny Burstein also scores in the smallish role of Bonaparte's trainer, Tokio. "I love that character, and I saw the potential in it," he said. "Of course I'm ridiculously biased, but I think he's kinda the heart and soul of the show. I think everybody should shut up and listen to Tokio. He's the voice of reason — he really is — and he actually has Joe's best interests at heart. That's a rare thing in this show. Everybody seems to want something from him, but Tokio just wants him to be happy and be a complete person, not half a man.

"I guess that the massage scene with Joe at the end of Act Two is my favorite scene for myself, but, honestly, anytime that Tony Shalhoub or Anthony Crivello or Ned Eisenberg are on that stage — those really are my favorite times."

Daniel Jenkins, a Drama Desk nominee for Big and Big River, takes the cake for landing big in a bit role. In 20 words or less, he makes a devastating hole in the play.

Big parts or bit parts, Odets' son, Walt, embraced it all. "This is the best production of Golden Boy I've ever seen," he announced happily. "It's superb — with that terrific, detailed, wonderful cast sorta end to end. I'm very impressed — and very exhausted. You know, I've been seeing this show every night since previews started, and it is emotionally so exhausting. There's an intensity about it, and I feel drained every time I come out of there — and I'm not even doing the work of the actors."