*

Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim's West Side Story opened at the Winter Garden Sept. 26, 1957, and almost immediately worked its way to classic status. The show was recorded by Goddard Lieberson of Columbia Records in what was then the new stereophonic process, and the original cast album — featuring Larry Kert, Carol Lawrence and Chita Rivera — remains the primary recording of the score. (This seems to have been Broadway's first stereo cast recording, quickly followed by The Music Man. The 1956 musicals Bells Are Ringing and Candide were recorded in both mono and stereo, but the stereo versions weren't released until 1958 and 1963, respectively.

Other recordings of the score have come along, most notably Bernstein's own high-powered studio cast album of 1984. What could and perhaps should have been an authoritative version turned out to be several steps down from the original. Star casting catering to the crossover trade, with José Carreras as Tony and Kiri Te Kanawa as Maria, depleted the theatricality of the songs; and the orchestra — self-conducted by the composer — lacked the brilliance of the original. (The same thing happened with what was intended to be an improved-and-finished version of Candide, conducted by Bernstein in 1989 but released after his death in 1990.) As has been seen elsewhere, a seventyish author's changes to work that he created in his prime are not necessarily definitive improvements.

Michael Tilson Thomas — a protégé and friend of the composer, with close links to Bernstein's work and family — has brought us a new, complete West Side Story [SFSmedia]. This was performed in concert by the San Francisco Symphony at Davies Symphony Hall in 2013 with an expanded orchestra and a full cast. Here, finally: an expert, modern-day recording of the score, overseen and authorized by the Bernstein estate, to supplement the excellent but technologically (relatively) primitive original from 50-odd years ago.

(This is heralded as "the first-ever concert performance of Leonard Bernstein's complete score," whatever that is supposed to signify. Numerous songs and dances from West Side Story have been performed in concert, of course. This recording includes such items as the Taunting Scene, which I don't expect is ever performed anywhere other than in a staged production; but you won't hear other sections, like the incidental music under dialogue that stretches between "Cool" and "One Hand, One Heart.") The resulting San Francisco West Side Story is quite good, yes. The orchestra is strong, mostly, and often exciting (although the percussion section occasionally stands out, and not in a helpful manner). The 1957 album has a significantly smaller orchestra, of 28 or so; but that was the original Broadway orchestra, recorded just three days after the New York opening. There is an excitement and tension that comes across on the original recording with vibrant authenticity, which we don't get from the San Francisco recording.

| |

|

|

| Alexandra Silber |

Using full complements of flutes, clarinets and oboes removes the need for the reed players to endure a two-hour marathon every performance; and in places where the orchestrators used only one flute, you can augment it with your whole symphonic flute section. The extensive liner notes do not include a musician list, so it's hard to say just how large the orchestra is; but even if there are a dozen San Francisco reed players sitting in the hall, the orchestrators only provided four separate parts to be played at any one time.

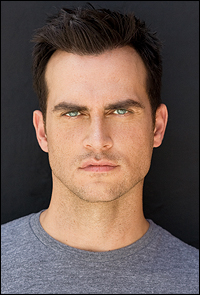

Cheyenne Jackson as Tony and Alexandra Silber as Maria acquit themselves well, although this is a sweetly-sung West Side with plenty of vibrato; while they hit their notes and offer reasonably accomplished performances, they don't especially seem to feel their roles or live them. To paraphrase the West Side Story lyricist in one of his subsequent outings, they "got the notes, yeah, but not the guts." While the original Anita, Rivera, has rarely been surpassed, I don't know that the performances of Kert or Lawrence were ever considered brilliant. Still, their renditions of the songs — "Something's Coming," "Maria," "Tonight," "One Hand, One Heart," "I Have a Love" and their sections of the "Quintet" — simply sound right to my ears, at least after hundreds of hearings of the 1957 recording. Jackson and Silber don't compare. Jessica Vosk, the current Anita, sounds impressive enough to make me want to see her perform the role onstage.

| |

|

|

| Cheyenne Jackson | ||

| photo by Karl Simone |

This takes us back to our initial reaction to this earnest and musically intelligent recording of the score. Quite good, with high spots here and there; but Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony clearly intended to give us a definitive new recording that could take the place of the original. If you ask me to combine the two into a "best" West Side, I would select sections of this new recording's "Dance at the Gym" and Ballet. The rest, including every one of the vocals, would be all 1957. *

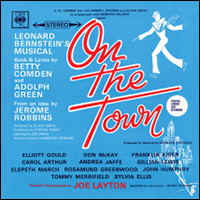

With Bernstein on our mind, we turn our ears to the 1963 London cast album of On the Town. This was Bernstein's first musical theatre work, which burst upon an unsuspecting Broadway at the tail end of 1944 with book, lyrics, and featured performances by Betty Comden and Adolph Green.

| |

|

|

| Cover art |

On the Town was successful enough that it wasn't totally overlooked. Decca, the label of Oklahoma!, released an album of six songs from On the Town. This included three of the original leads, comedienne Nancy Walker singing "I Can Cook, Too" and "Ya Got Me" plus Comden and Green singing "Carried Away." Their tracks captured some of the exuberance of the show and their performances. Otherwise, Decca brought in Mary Martin — star of Broadway's other hit musical of 1943, One Touch of Venus — for unsatisfying pop versions of the big two ballads, "Lucky to Be Me" and "Lonely Town."

The show's long-term prospects were not enhanced by the so-so 1949 M.G.M. film adaptation, which toned down the brashness and deleted much of Bernstein's score. A small-scale 1959 Off-Broadway run — directed by Gerald Freedman, Robbins' assistant director on West Side Story — lasted two months. (The Gabey in this production was Harold Lang, who had created the role of one of the sailors — opposite Robbins — in the Bernstein/Robbins ballet Fancy Free, from which On the Town was developed.)

The show was more or less rescued in 1960, when Columbia Records — thanks to the sales results of West Side Story and their ongoing relationship with Bernstein as conductor of the New York Philharmonic — decided to fund a full studio cast album. With Comden and Green recreating their roles, Bernstein himself on the podium, and top musicians playing the original orchestrations by Hershy Kay (with Don Walker, Elliott Jacoby and Ted Royal), a new generation of listeners got the chance to hear just how vibrant On the Town is. Broadway is about to see a third big-budget revival, and I don't suspect any of these productions would have happened were it not for the 1960 recording.

Before the show first returned to Broadway in 1971, though, it received a belated West End premiere in 1963. The long out-of-print cast album of that On the Town [Masterworks Broadway] has now been rereleased. It turns out — perhaps surprisingly, given the poor reception and short run of the production — that it is pretty good. The orchestra can't be expected to compare with the playing on Bernstein's recording, and the Walker-Comden-Green trio are definitive (even if they are middle-aged adults portraying innocent 20 year-olds).

In London, at least, we get relatively young actors playing the leads. The Green and Comden roles are played by Elliott Gould (from Arthur Laurents' just-closed Broadway musical I Can Get It For You Wholesale) opposite a perfectly fine Gillian Lewis (from the original cast of Julian Slade's Salad Days and Free As Air). Franklin Kiser (soon to go into Ben Franklin in Paris) and Don McKay (Tony in the London West Side Story) are the naïve Chip and the love-struck Gabey. Conductor Lawrence Leonard (of the London West Side Story) apparently had the opportunity to study Bernstein's 1960 recording measure-by-measure, and the good sense to replicate the tempos and accents. So while this On the Town doesn't match the prior recording, it is a perfectly listenable alternative.

That is, except for the one Big Problem. Somebody — I expect director/choreographer Joe Layton, who had choreographed the 1959 Off-Broadway production — apparently decided that the gal taxi-driver Hildy should be played as a cartoonish, man-eating tigress. Nancy Walker, for whom the role was created, was a cartoonish caricature, yes; but she was a delectable one who turned tender as the three sailors' 24-hour leave on the town expired. In London we get the sledgehammer approach, not only in Carol Arthur's playing of the role, but in the reconfigured orchestration of "I Can Cook, Too." Don Walker's original chart is a 1940s explosion of joy, cookin' with gas; the 1963 version, from an orchestrator unknown, is simply loud and clashingly brash. Poor Ms. Arthur is left sounding pretty much lost, although I suppose she was only doing what she was directed to do.

(This is the same Carol Arthur who played Edith, the maid, in the 1964 High Spirits and later replaced Marilyn Cooper in Woman of the Year. When Larry Gelbart introduced me in 1989 to Arthur and her husband Dom DeLuise, he went out of his way to tell me that she was a seriously funny actor. And Larry Gelbart ought to know.)

The other major change on the recording is an extended opening to the Finale, giving the three sailors something more to sing before the clock strikes six and their 24-hour leave ends. Whether this material is from the original, from 1959, or written for London, I don't know; either way, it is not an improvement. There are also numerous small cuts within the dance and ballet numbers, but conductor Leonard gives us a fair and lively representation of Lenny, Betty and Adolph's first musical.

(Steven Suskin is author of "Show Tunes", "The Sound of Broadway Music: A Book of Orchestrators and Orchestrations," "Second Act Trouble," the "Broadway Yearbook" series and the "Opening Night on Broadway" books. He also writes the Aisle View blog at The Huffington Post. He can be reached at ssuskin@aol.com.)

-Matthew-Murphy.jpg)